Continuity and Change in Premodern Islamic Pedagogy (8th-18th Centuries)

Uncovering the Arabic Educational Heritage for Contemporary Societies

Miskawayh

ca. 932-1030

1 Life and Scholarship

2 Scholarly Network

3 Contribution to Educational Thought

3.1 Learning and Character Refinement

3.2 Instruction in Virtues

3.3 Methods and Structure of Education

3.4 Responsiveness to Moral Education

3.5 Early Childhood Instruction

3.6 Higher Learning

3.7 The Philosophical Study Program

4 Essential Educational Principals

5 Significance for Contemporary Education

6 Reception in Later Scholarship

Reproduced with kind permission of Bridgeman Images Berlin.

Abū ʿAlī Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Yaʿqūb al-Khāzin (“The Treasurer” or “The Librarian”) was born between 932 and 936 in the city of Ray, the Rhages of antiquity, near Tehran. He died in 1030, almost a hundred years old, probably in Isfahan. The name by which this scholar is best known, Miskawayh, is said by some to be the Arabicized form of the Persian Miskōye or Mushkōye, a suburb of the city of Ray where his family probably came from; others suggest the nickname was applied to him in the sense of “the musk-like” or “the musk-scented” (Yaqūt, Muʿǧam iv: 543; al-Ṭabarī, Tārīkh viii: 392).

Whether or not Miskawayh was a Shiʿi, as some later Shiʿi sources claim, is still a matter of discussion in modern scholarship. On the one hand, it is relatively certain that Miskawayh grew up and was active in the predominantly Shiʿi milieu of the Buyid dynasty’s domain of power. On the other hand, there is no place in Miskawayh’s scholarly oeuvre where he explicitly addressed essential Shiʿi topics. Instead, we encounter in his works, first and foremost, an author who thinks across denominational boundaries and is well-versed and productive in a great variety of scholarly disciplines (Günther/El Jamouhi, “Der Moralphilosoph” 10-1).

1 Life and Scholarship

Miskawayh was a highly productive Muslim thinker, writer, and courtier. Well-acquainted with various branches of scholarship of his age and open-mindedly embracing the cosmopolitism of Abbasid society, Miskawayh wrote on a wide array of academic subjects. Foremost among these were philosophy and history. However, his interests extended to literature, medicine, psychology, alchemy, and cooking.

Miskawayh’s intellectual reputation rests principally on two works: his celebrated manual of philosophical ethics, Tahdhīb al-akhlāq wa-taṭhīr al-aʿrāq (The Refinement of Character Traits and the Purification of Natural Dispositions), and his universal history, Tajārib al-umam (The Experiences of the Nations).

Miskawayh’s works testify to his academic resourcefulness and originality. At the same time, they reveal how much this classical Muslim thinker was attracted to classical Greek thought, especially that of Plato, Aristotle, and the Neoplatonists. In addition, Muslim predecessors such as the philosophers Yaʿqūb b. Isḥāq al-Kindī (d. ca. 870) and Abū Naṣr al-Fārābī (d. 950), as well as the littérateurs Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ (d. ca. 756) and al-Jāḥiẓ (d. 869) also appear frequently as references in his writings. The Persian cultural tradition, however, into which Miskawayh was born and which was a constant mainstay, both personally and intellectually, was an essential inspiration for him throughout his life.

2 Scholarly Network

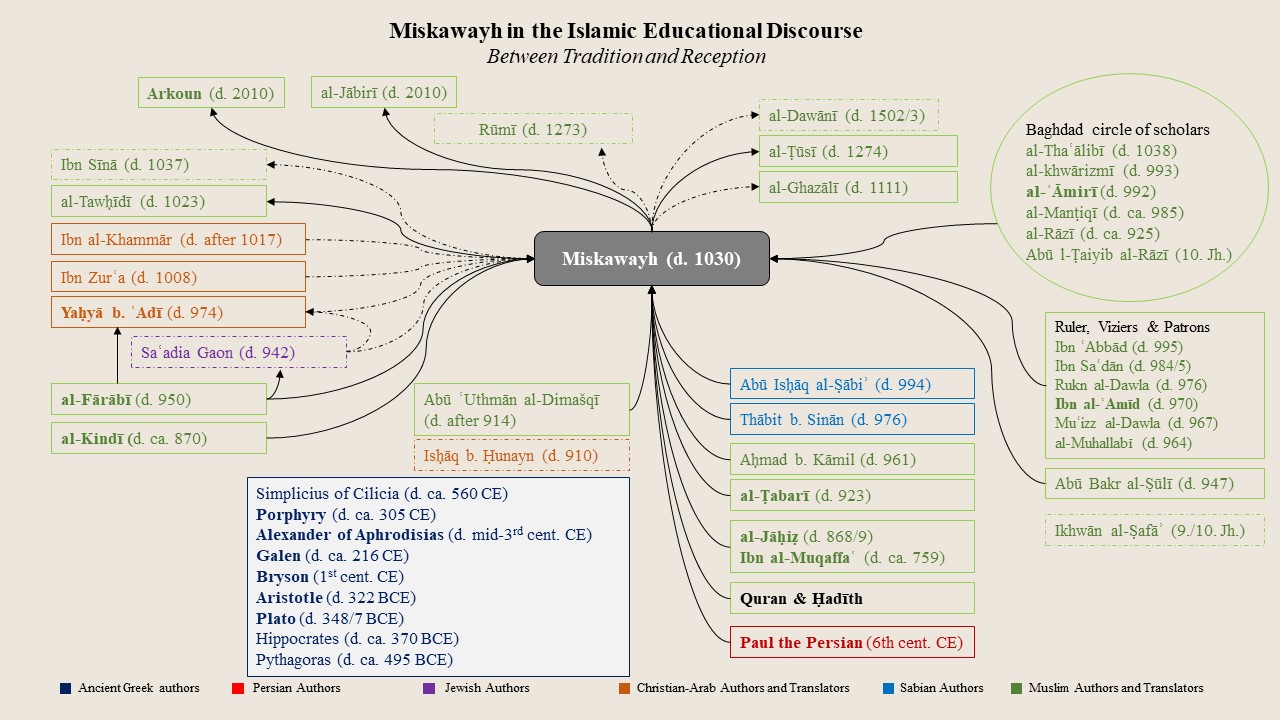

Miskawayh’s scholarly output as a whole is a striking testimony to this classical Muslim scholar’s comprehensive reception of ancient and contemporary philosophical works written by ancient Greek as well as Christian Arabic and Muslim authors. For his historiography, he also relied on 10th-century historians who were Sabians, that is, members of a community that adhered to an ancient Semitic polytheistic religion but whose elite was largely Hellenized (de Blois, “Ṣābiʾ” 672-5).

This diversity of sources and authorities on which Miskawayh relied in the context of the scholarly networks of his time, and the reception of his thought in later Muslim scholarship, is illustrated in Figure 1 at the end of this entry.

3 Contribution to Educational Thought

Several of Miskawayh’s writings offer detailed advice on learning. Most significant in this regard are his major works, Tahdhīb al-akhlāq wa-taṭhīr al-aʿrāq (The Refinement of Character Traits), Tartīb al-saʿādāt wa-manāzil al-ʿulūm (Ordering the Degrees of Happiness and the Ranks of Sciences), and Ādāb al-ʿArab wa-l-Furs (Morals [and Wisdom Sayings] of the Arabs and the Persians). Concerning this latter work, moreover, Miskawayh stated that he composed this book for a specific reason, assembling therein numerous pieces of wisdom

for the young men (aḥdāth) to educate themselves with them, for the learned to remember what had come before them of wisdom and knowledge (al-ḥikam wa-l-ʿulūm) [and, in addition, as a] rectification of myself and of whoever may be rectified by it after me.

لِيرتاضَ بها الأحداثُ ويتذكّر بها العلماء ما تقدّمَ لهم من الحِكَم والعلوم. والتمستُ بذلك تقويم نفسي ومَن يتقوّى به بعدي

(Miskawayh, Ḥikma 6)

His monumental work on history, The Experiences of the Nations, from which he intended that people should learn for their present and future, has its vigorous educational orientation already explicit in the title.

Two more pedagogically significant points are included in his The Refinement. One is Miskawayh’s recommendation that individuals aspire to attain noble, stable, and authentic character traits, as those will help them act straightforwardly and successfully in society (Miskawayh, Refinement 5). The other is his assertion that people should make every effort to reach this high ethical and societal goal through a didactically “ordered, gradually advancing instruction” (ʿalā tartīb taʿlīmī; Miskawayh, Tahdhīb 1). This way of learning would provide a solid basis for human beings as they achieve a state of development at which they, first, take an interest in the affairs of society; second, act sensibly for their own and the society’s well-being; and third, do so naturally and voluntarily, without any need for prior deliberation.

3.1 Learning and Character Refinement

In the preamble to The Refinement, Miskawayh defined the primary purpose of this writing and added an instructive outline of his study questions and research strategies. According to these, the objectives outlined in this book are:

Our objective in this book is to acquire for ourselves such a character that all our actions issuing therefrom may be good and, at the same time, may be performed by us easily, without any constraint or difficulty. This object we intend to achieve according to an art, and in a didactic order. The way to this end is to understand, first of all, our souls: what they are, what kind of thing they are, and for what purpose they have been brought into existence within us – I mean: their perfection and their end; what their faculties and aptitudes are …

غَرَضُنا في هذا الكتابِ أنْ نُحَصِّلَ لأنفُسِنا خُلُقًا تَصدُرُ بِهِ عَنّا الأفعالُ كُلُّها جميلةً، وتكونُ معَ ذلكَ سَهلةً عَلينا لا كُلْفَةَ فيها ولا مَشَقّة، ويكونُ ذلك بِصناعةٍ وعَلى ترتيبٍ تَعليميٍّ. وَالطريقُ إِلى ذلكَ أنْ نعرفَ أَوّلًا نفوسنا: ما هي؟ وأَيُّ شيء هي؟ ولأيِّ شَيءٍ أُوجدَت فينا، أعني كَمالَها وغاَيتَها وما قُواها وَمَلَكاتُها

(Miskawayh, Tahdhīb 1; Miskawayh, Refinement 1)

With this passage, Miskawayh aimed to provide his readers with guidance and instruction vital to moral education. Although, in his view, humans are the noblest beings in creation, they still need education to develop their humanity, especially concerning what is good and what is evil. Humans acquire an authentic and lasting character through a process of learning that is measured in its steps and combines intellectual with moral education. This understanding of the fundamentally ethical grounding of all learning relates directly to the Quranic statement cited above.

However, Miskawayh understood this idea in a rationalist way, firmly rooted in Greek thought. It is a perception that underlines the strong interdependence between ethics, education, and human development in a manner that Socrates already described when he famously stated, “I believe that we cannot live better than in seeking to become better, nor more agreeably than having a clear conscience” (Douglas, Forty 337).

3.2 Instruction in Virtues

In The Refinement, Miskawayh used a simile to teach his audience that one can make either a valuable but also a worthless sword out of the same metal — depending on one’s mental and physical abilities and determination. The betterment of a human’s “substance is entrusted to man and depends upon his will” (Miskawayh, Refinement 35). While God created humankind and entrusted them with the ability to learn and become better, it is up to each individual to use this God-given capacity through art and culture.

Miskawayh offered three observations in this context that bear implications for learning:

- The means to accomplish the task of acquiring virtues is a specific art or science (ṣināʿa), namely, “the art of character training which is concerned with the betterment of the actions” of humans as humans―man qua man; indeed, it is “the most excellent of the arts” (Miskawayh, Refinement 33);

- The best method to reach this aim is a didactically well-thought-out, measured instruction (tartīb taʿlīmī); and

- The objective of this process is to learn how to refine one’s character. The ultimate state that a person may aspire to reach in this regard is a state of spontaneous performance, where good acts are accomplished readily, naturally, and without prior deliberation.

Miskawayh again draws on an old Greek idea, according to which an act’s aim or end (ghāya) may influence—and even define—the beginning or principle (mabdaʾ) of an undertaking. Accordingly, the objective of an act may come to characterize the action itself. Therefore, if the ‘objective’ of a deed is virtuous, the ‘action’ that leads to it may—or would even necessarily—acquire the quality of being virtuous. Translated into an educational context, this means that if the aim of learning is virtuous, learning is likewise a virtuous activity.

3.3 Methods and Structure of Education

Defining the educational objectives to be achieved by specific teaching and learning methods, the subject matters these methods involve, and the social classes for which they are designed are of particular concern to Miskawayh. He highlighted, for example, that ethical instruction and moral betterment must precede any other form of learning activity, whether intellectual or spiritual. This is particularly true for anyone acquiring knowledge in philosophy, religious law, or prophetic traditions. Attaining virtue cannot be achieved by

impeding and neglecting the cognitive faculty, by disregarding the investigation which is proper to reason, and by being satisfied with deeds that are neither civic nor in accordance with the demands of discernment and reason.

بِتَعطيلِ القوّة العالِمَةِ وإِهمالِها، وبِتَركِ النَّظرِ الخاصِّ بالعَقلِ واِكتفائِهم بِأعمالٍ لَيست مَدَنِيّةً ولا بِحسبِ ما يُقسِطُهُ التَّمييز والعقلُ

(Miskawayh, Tahdhīb 91; Miskawayh, Refinement 81)

In other words, investigation and close examination (baḥth and naẓar), sound thinking (fikr ṣaḥīḥ), and correct reasoning (qiyās mustaqīm) are appropriate and, indeed, the required intellect-based methods and tools even in categories of learning that place ethical instruction first. Such education will help the young to control their natural temper in situations of an emotional challenge, and it will eventually serve them in finding the way to “the high rank of philosophy” and “seeking proximity to God” (Miskawayh, Refinement 35, 55-6).

3.4 Responsiveness to Moral Education

Edification in ethics takes place on two levels:

- On a fundamental and morally unobjectionable level: The acquisition of fundamental morals eventually enables an individual to enjoy a good and pleasant life, gain a fine reputation, and have virtuous friends.

- On a higher and more uncompromising level: This relates to the idea that there is a kind of moral learning and refinement that goes beyond what is related to worldly goods and ensuring bodily well-being. These actions eventually enable the individuals to delight in the grace of God and prepare themselves for the eternal world and everlasting happiness in the hereafter.

However, teachers must adjust moral instruction to the level of their students’ intellectual and physical capabilities. For example, youth with a “rational soul” (nafs nāṭiqa), i.e., those who fully use their intellect, can be expected to become morally decent individuals. Instruction taking a rational approach may be unsuitable, however, for educating those with a strong “irascible soul” (nafs ghaḍabiyya) or even a dominant animal soul (nafs bahīmiyya).

The latter refers to people who are interested only in satisfying their whims and are unresponsive to the usual methods of instruction and education (taʾdīb). It might even seem impossible to discipline them at first glance.

This, however, is a false impression, according to Miskawayh. In such cases, nothing but additional patience and particular attentiveness are required from the educator. Also, as “problem children” grow up and mature, they may become aware of their appalling conduct and become more receptive to moral instruction. Thus, there is always hope that those youth will gradually depart from their former character and “return to the ideal way through repentance, association with good and wise men, and the diligent pursuit of philosophy” (Miskawayh, Refinement 51-2, 57). In short, every child is potentially educable.

Miskawayh takes a line of thought here concerning a learner’s different degrees of responsiveness to discipline, learning, and attaining virtues. Some of these ideas he presented in The Refinement when discussing theories of Greek authorities, naming the Stoics in particular (with their belief that all humans are “created good by nature”) as well as Galen (who suggested that some people “are good by nature, others are bad by nature, and still others fall between the two” categories), and Aristotle (who is referred to with his concept that humans “may, through discipline, become good”) (Miskawayh, Refinement 29-31).

Addressing the issue of students who do not, or only slowly, respond to a teacher’s efforts to instruct them, Miskawayh recommended deceleration in providing learning content. Showing empathy instead of adding pressure was the right strategy here. In this way, the teacher could reach those more challenging students and help them participate in the educational process meaningfully.

3.5 Early Childhood Instruction

Early childhood education is of particular concern to Miskawayh. The ethical components are again at the forefront here, as our author specified that “affection, the accounts of concord, and the benefits which all people gain through love and fellowship” are essential and helpful in instructing the young. In contrast, “the stories of wars, hatred, revenge, and rebellion” are utterly unfit for teaching children (Miskawayh, Refinement 140).

Regarding the sequence of early childhood instruction, the natural path of things must be followed. One should begin with the following:

- Basic physical instruction (on nourishment and eating habits); then proceed to

- Emotional instruction (on human disposition such as anger and the love of honor), and

- Intellectual instruction (to make children understand the value of knowledge and science), eventually complemented by

- Psychological and health instruction (Miskawayh, Refinement 33, 56)

These last steps should be taken, as Miskawayh clarified, “when the boy understands this and grasps its truth, and then becomes accustomed to it by continuous practice” (Miskawayh, Refinement 56).

If punishing a child is unavoidable, the penalty must never be verbally too explicit (when “rebuking”) or physically too excessive (when “flogging”). Such handling leads to nothing but the opposite of what was intended. The child even might grow accustomed to this kind of penalization, becoming even more ill-mannered, and perhaps even entirely irresponsive to education. Therefore, the parents’ first and most important responsibility is instructing their children in good manners (Miskawayh, Refinement 32).

Parental instruction in ethics at the time of childhood must agree with and be underscored by basic education in religious law, as Miskawayh emphasized. Indeed, the child must be familiarized with the law at this early stage. Thus, the child becomes accustomed to its commands and more easily comprehends the motives and the causes of things later when studying philosophy, for example. Young people may realize that much of what they learned as young adults is in agreement with what they had been taught in terms of habits and morals as children, to the effect that the learner’s “judgment becomes firm, his insight penetrating, and his determination effective” (Miskawayh, Refinement 114).

Again, instruction of any of these kinds must take the intellectual and physical capabilities of the young into due account, for some children are more receptive than others to learning and character formation; some acquire it faster, and others more slowly (Miskawayh, Refinement 31).

In general, Miskawayh saw learning as a life-long process. It requires modesty and humility more than anything else. Even when the learner grows up, advances significantly in learning, and eventually becomes

unique and eminent in knowledge, then this person must not pride himself in what he has achieved, nor should these achievements cause him to cease seeking beyond. For knowledge has no limit, and above every man of knowledge, there is One who knows [much more].

وإن كان حافظ هذه الصحّة قد توحّدَ في العلم وبرعَ، فلا يحملنَّهُ العجب بما عندَه على تركِ الازديادِ، فإنّ العلم لا نهاية له، وفوقَ كلّ ذي علمٍ عليم

(Miskawayh, Tahdhīb 179; Miskawayh, Refinement 160, in reference to Quran 12:76)

3.6 Higher Learning

In Miskawayh’s terms, higher education includes teaching philosophical (ḥikmī), metaphysical (ilāhī), and religious (sharʿī) components as much as it involves rational, sensorial, psychological, and spiritual aspects.

First, his concept that the philosophical-ethical study program proceeds gradually is worth close examination. It begins with practical things, such as conduct in religious law, and continues with studying more theoretical fields, such as ethics and logic. This is followed by arithmetic, geometry, and other natural sciences, for comprehending the physical world and language studies, and for learning to think and express oneself correctly and reasonably.

Philosophy (falsafa) is the most advanced stage of this course of academic education (Miskawayh, Refinement 44-5, 114, 154), with the ultimate objective of attaining complete happiness and human perfection.

Metaphysics “does not fall within the scope of the art of the refinement of character” (Miskawayh, Refinement 62). However, students will become familiar with it as they advance in their ethical-philosophical education. And indeed, metaphysics is said to represent the most sophisticated activity in a comprehensive curriculum, in which acquiring knowledge about the Divine signifies “the culminating rank among the sciences” (Miskawayh, Refinement 36).

Second, religious education centers around the (rational) acquisition of knowledge of God to obtain certainty (yaqīn) in spiritual matters. It is based on studying normative religious traditions (sunna). However, it also relies on essential ethical components, such as the learners’ need to familiarize themselves with what is good and what is bad, and the meanings of forbearance, virtuousness, and equitableness (Miskawayh, Ḥikma 5-6; Miskawayh, Wisdom 326-7).

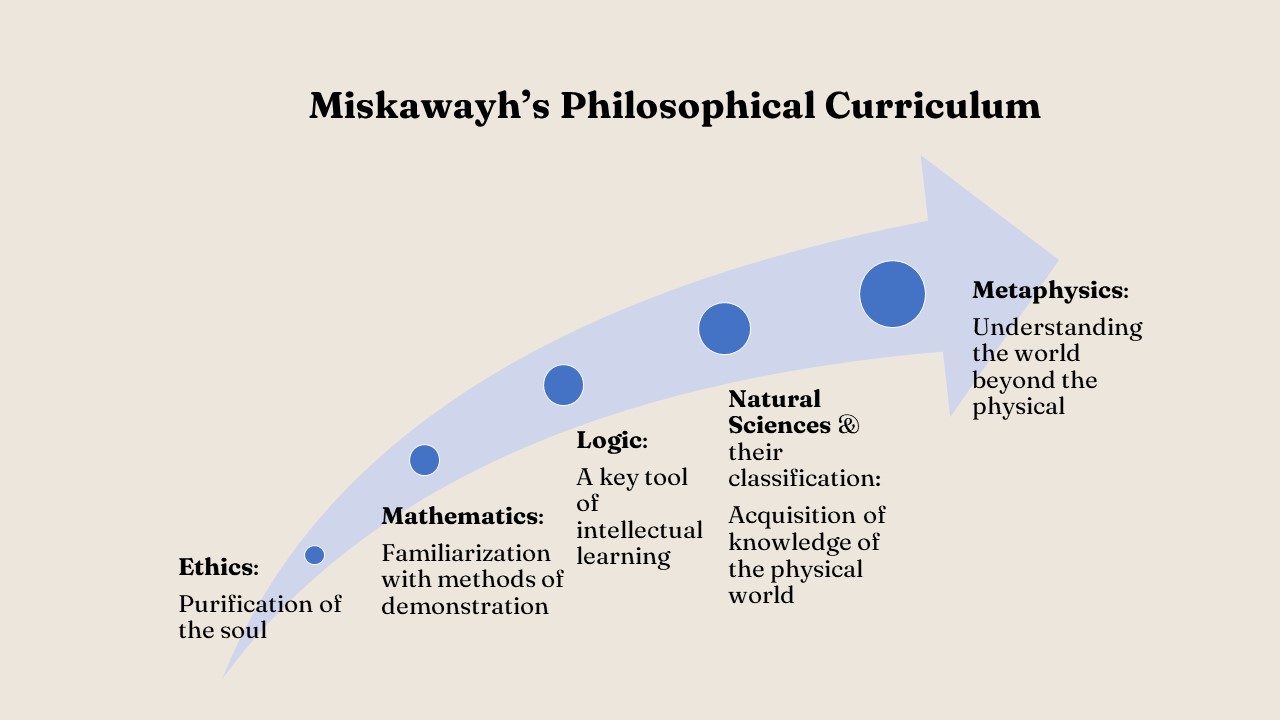

3.7 The Philosophical Study Program

In his works on ethics, the secular sciences and worldly affairs are central to Miskawayh’s conception of learning. Indeed, he acknowledged on several occasions in these works that―due to the ethical-philosophical focus of the respective texts―he did not wish to deal with the desire for the divine (shawq ilāhī) and divine knowledge (maʿrifa ilāhiyya). He made explicit that metaphysical education “does not fall within the scope of the art of the refinement of character. … But you will come to know it if, God willing, you will attain this rank” of moral advancement and intellectual insight, as indicated in respective previous passages (Miskawayh, Refinement 62). In other words, learning in the ethical-philosophical context primarily means acquiring knowledge of philosophy. Progress on this path is made in two steps, as our author noted (Miskawayh, Theology 95; Miskawayh, Refinement 62):

- The learner begins with the study of logic, an instrument for correct understanding and instinctive reason.

- One proceeds to the study of the natural sciences, which leads to an understanding of the physical world, including knowledge of the creatures in it and their natures (Miskawayh, Theology 95, 137, 145; Miskawayh, Refinement 62).

For philosophically inclined learners, Miskawayh specified the disciplines worth studying and the sequence in which these studies should take place. The following picture emerges from this discourse:

- At an early age, practical instruction is the focus. Young people should become familiar with the conduct in religious law (adab al-sharīʿa) and the observance of its duties and requirements until they endorse them and make them their habits.

- At a later stage, theoretical instruction will follow. It essentially relates to studying the works of ethics (kutub al-akhlāq). Indeed, the rational demonstrations (barāhīn) provided in these books foster cognition of what good morals mean, so the young will be sufficiently equipped intellectually and encouraged to adopt them emotionally.

- Arithmetic (ḥisāb) and geometry (handasa) are further recommended disciplines. Knowledge of these study areas helps learners in their acquisition of accurate speech (ṣidq al-qawl) and correctness in demonstration (ṣiḥḥat al-burhān). Also, arithmetic and geometry (two of the four subjects of the ancient liberal arts education, the quadrivium, next to music and astronomy), are essential preparations for the study of

- Philosophy (falsafa). This last stage of stud-ying constitutes the peak of the ethical-philosophical study course (Miskawayh, Refinement 44-5, 114, 154).

The ultimate objective of Miskawayh’s philosophical learning program―complete happiness and human perfection―can be achieved after a person “has acquired a sound knowledge of all the parts of philosophy and mastered them gradually.”

For more details concerning this educational endeavor, the author directed the reader of The Refinement to his earlier work, Ordering the Degrees of Happiness (Tartīb al-saʿādāt) (Miskawayh, Refinement 81). This book is crucial in this context, as the author stated, for failure “to investigate and to exercise one’s soul with the teachings … enumerated in Ordering the Degrees of Happiness (Tartīb al-saʿādāt) may lead to stupidity (ghabāwa) and ignorance (jahl)” (Miskawayh, Refinement 110).

Miskawayh put two additional points of consideration in the forefront: First, his earlier book, The Degree of Happiness, contains (as its full title indicates) a more detailed study program; and second, this more comprehensive course of learning can help the learner attain enlightenment and enable the student to lead an ethical life. And indeed, the reader so directed to The Degree of Happiness encounters in the second part of this book an elaborate discussion of specific arts and sciences (ṣināʿāt), along with specific recommendations on how to study them, for “he who follows this course, is indeed the happy and the perfect one,” as Miskawayh affirmed (Marcotte, “Ibn Miskawayh” 149).

Furthermore, in The Degree of Happiness, the concept is highlighted that ethical instruction is propaedeutic to all other studies. Here Miskawayh expressly drew on Aristotle for his idea of acquiring two constituents of wisdom (ḥikma): one theoretical (naẓarī) and the other practical (ʿamalī) (Miskawayh, Refinement 117).

Our author also acknowledged that the study plan he specified represents Aristotelian thoughts which he had drawn from a book (kitāb) by Paul the Persian, a 6th-century East Syrian theologian, philosopher and Aristotle commentator (Miskawayh, Tartīb 117; cf. Marcotte, “Ibn Miskawayh” 149; Gutas, “Paul” 232-8; Pines, “Aḥmad” 121-9; Arkoun, L’humanisme 227-33). In other words, Miskawayh acknowledged that Aristotle and the philosophical tradition that builds on his work (accessible to Miskawayh through the writing of the Persian Christian scholar Paul) are the primary sources and the foundation of his respective pedagogical ventures. The background of all this, as Miskawayh explained further, is that it was “he [Aristotle the Sage] who ordered the components of wisdom and classified them” (fa-innahu huwa alladhī rattaba al-ḥikam wa-ṣannafahā) (Miskawayh, Tartīb 117).

The arts (ṣināʿāt) that Miskawayh primarily endorsed as endowing learners with the knowledge that is necessary to reach certainty (yāqīn) are those of the lower division of the Seven Liberal Arts of Antiquity, the Trivium. Miskawayh identified those as:

- Logic (manṭiq)

- Grammar (naḥw)

- Rhetoric (or prosody, ʿarūḍ)

The method of approaching these arts to benefit the most from them is, as Miskawayh advocated, deduction by analogy (qiyās) (Miskawayh, Tahdhīb 118-21, 126). He also highlights that intellectual learning is the critical activity for organizing the individual’s mind and thought to enable humans to make sense of their world. In other words, creative thinking is held to be an orderly process that makes an individual “a wise person who possesses perfect happiness” (al-ḥakīm al-saʿīd al-kāmil al-saʿāda). The steps to reach this stage include perseverance in performing activities such as:

- Empowerment of the mind (dhihn)

- Discriminative discernment and judgment (tamyīz)

- Understanding of things as they really are (ḥaqāʾiq al-umūr)

- Execution of action based on what has been learned (infādh mā ʿalima ʿamalan) (Miskawayh, Tartīb 115; cf. Rizek, “An Art” 270-1).

This process of learning and human advancement involves the mind and the body. Its first step relates to acquiring knowledge (ʿilm) as the learning process’s investigative or theoretical component (juzʾ al-naẓar). This intellectual study activity constitutes the basis for all other deeds and must precede them. It is followed by action (ʿamal) as its practical component (juzʾ al-ʿamal). Moreover, excellent discernment and a powerful mind are always required for cognizance (maʿrifa) (Miskawayh, Tartīb 115).

Miskawayh embedded these considerations in learning theory and study practice in a detailed discussion of certain books which Aristotle had devoted to the different levels of the soul’s contentment (marātib iqtināʿāt al-nafs) and the classification of the sciences (taqsīm al-ʿulūm). Our author explicitly presented the Arabic titles of these writings and surveyed their main contents. Toward the end of The Degree of Happiness, Miskawayh summed up his recommendation of a Greek-inspired, philosophical curriculum as follows:

Some of Aristotle’s disciples from among those teaching (al-mudarrisūn) his books believed that the one who studies them (al-mutaʿallim lahā) should start with the books on ethics (kutub al-akhlāq) in order to refine his soul, purify it from the distress of desires, and lighten for them their obstructions so that the learner will be able to receive wisdom …. Then he should look into subject matters contained in the books of mathematics (kutub al-taʿālīm) in order to familiarize himself with the methods of demonstration (ṭuruq al-burhān) …. Then he should look into logic (al-manṭiq), which is a tool for all that he wishes to achieve; then into physics (the natural sciences) and that which derives from them (al-ṭābīʿiyyāt wa-mā baʿdahā) according to the classification of that which was presented earlier, until he arrives at metaphysics (i.e., the matters that do not reside in material things, al-umūr allatī laysat fī mawādd).

وقد رأى بعض أصحاب أرسطو من مُدَرّسي كتبه أن يبتَدِئ المتعلِّمُ لها بكتب الأخلاق لتتهذّب نفسه وتصفوَ من كدر الشهوات ويخفّ عنها أثقال عوارضها، فتُمَكَّنَ من قبول الحكمة …. ثمّ ينظر في شيء من كتب التعاليم ليعرف طريق البرهان …. ثمّ ينظر في المنطق الذي هو آلة في جميع ما يقصده. ثمّ ينظر في الطبيعيّات وما بعدها على الترتيب الذي تقدّم، إلى أن يصل إلى الأمور التي ليست في موادّ

(Miskawayh, Tartīb 126)

4 Essential Educational Principals

Miskawayh considered ethics a foundational branch of knowledge. He also saw ethics and learning as closely interconnected components that might lead humans to perfection and happiness. Miskawayh emphasized that:

- Progress in learning and development as an individual and a member of society requires learners to strive to understand the complexities of their souls, i.e., what hinders them from growing and what makes them prosper (Miskawayh, Refinement 1). If one understands one’s soul to some degree, moral and intellectual education may follow and be expected to be successful. On this premise, “the art of character training” is considered “the most excellent of the arts” among the essential objectives of human advancement (Miskawayh, Refinement 33).

- Ethical learning and human development can only be effectively acquired if they are based on didactically sophisticated, measured instruction (tartīb taʿlīmī). If this learning is successful, the ultimate objective of character refinement can be achieved, and good acts will be accomplished readily, naturally, and without prior deliberation.

- Aspirational learning combines ethical and didactic components. It requires (a) observing real questions as the starting point of an investigation, (b) extracting the principal components from composite questions, and (c) analyzing evidence comprehensively and contextually. This approach will make genuine education (al-adab al-ḥaqq), human perfection (al-kamāl), and happiness (al-saʿāda) possible (Miskawayh, Refinement 41, 63-4, 70). Inspired by ancient Greek ideas, Miskawayh thus equated―by way of analysis and synthesis—virtuous education with virtuous actions (Miskawayh, Refinement 64).

- Humaneness and love are important for humanity. Although Miskawayh mentioned “the divine law” and “the right religion” in relatively neutral terms, it can be assumed that he fully honored the religious foundations of Islam. At the same time, he advocated using ancient philosophical and cultural traditions as principal sources for forming character and mind. This sensible, unprejudiced, and open-minded approach to education is extraordinary evidence of this thinker’s general pedagogical stance, which in today’s terms can be called ‘humanistic.’

5 Significance for Contemporary Education

Among Miskawayh’s views on learning, the following are distinctly universal and relevant to today’s educational contexts:

- Ethically speaking, Miskawayh advised teachers and parents to encourage and guide youth to embrace decent conduct instead of reproaching and correcting them for problematic behavior. Likewise, he counseled educators and parents to help children and adolescents to:

- associate with upright individuals, especially those of their own age;

- treat others with fairness, kindness, and respect; and, not least,

- learn self-respect.

Miskawayh also expressed the insight that (moral) instruction is not restricted to a particular stage in life, although it is most effective when it takes place at a young age (Miskawayh, Refinement 51-5, 116).

- Intellectually high-quality study material is said to be essential for progress in learning. This relates to both its moral and thematic contents. Furthermore, teaching should take place gradually (i.e., new teaching topics must be connected to previously explored themes) and memorizing what was learned should proceed to its oral presentation and thematic discussion. This eventually leads to a deeper understanding of the study material and human development. However, granting young people sufficient time to relax and play is also part and parcel of successful learning and teaching (Miskawayh, Refinement 45, 55).

- Moral and intellectual schooling must be connected with education about health and well-being. This includes instruction about healthy food and the close link between eating habits and the well-being of body, soul, and mind. Along with acquiring values, intellectual capabilities, and practical skills, health education helps young people to build positive relationships with others and lead healthy and fulfilled lives (Miskawayh, Refinement 52-3).

- Miskawayh accentuated the importance of the soul’s health―“a divine, incorporeal faculty”― more than once, as its strength is directly connected to the well-being of the body and the mind. Therefore, illness of the soul, which may express itself in anger and grief but also in passionate love or restless desire, must be taken seriously and treated to ensure progress in education and human development (Miskawayh, Refinement 157-8).

- Last but not least, throughout his scholarly oeuvre, Miskawayh treasured cultural wisdom as “the virtue of the rational and discerning soul” and “the knowledge of things divine and human” (Miskawayh, Refinement 16). As he saw it, wisdom is a source of knowledge and enlightenment. Cultural wisdom, irrespective of its origins in terms of time, location, ethnic identity, and faith―be it from the Greeks, Arabs, Persians, or Indians, for example―edifies present and future generations of young people as much as it does those already advanced in scholarship (Miskawayh, Wisdom 326). Furthermore, part of the lessons that wisdom teaches is that, in order to learn, intellectual engagement and the courage to inquire are just as important as respect for tradition and the natural course of life. Those of intelligence who adhere to these basic principles can expect to be successful in their development as human beings and be among the happiest people in the world (Miskawayh, Wisdom 339-41).

6 Reception in Later Scholarship

Much of Miskawayh’s ethical-educational thought was taken up, appraised, and incorporated in one way or another by later Muslim scholars. A towering figure in this regard was the theologian and mystic Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī (d. 1111), who relied on Miskawayh in his considerations of virtues and questions of learning. Unlike Miskawayh, however, al-Ghazālī moved in a new direction in that he contributed to the ethical discourse not from a rational but from a spiritual, mystical perspective.

Miskawayh’s probably best-known recipients and successors in the field of Islamic ethics, however, are Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (d. 1274), author of the well-known Akhlāq-i Naṣīrī (The Nasirean Ethics) and, for that matter, a strong critic of al-Ghazālīs ascetic ethics; and Jalāl al-Dīn al-Dawānī (d. 1274), author of Lawāmiʿ al-ishrāq fī makārim al-akhlāq (Flashes of Illumination on the Excellence of Moral Dispositions), also known as Aḫlāq-i Dawānī (The Dawanean Ethics), a work advocating the idea of harmony between philosophy and mysticism. However, where Miskawayh, in his moral deliberations emphasized ethics as such (akhlāq), the latter two scholars added discussions of the two other areas of practical philosophy: household management (tadbīr al-manzil) and statecraft (or politics, siyāsat al-madīna, siyāsat al-mudun).

While several more scholars in premodern times wove into their works educational ideas from Miskawayh (or, through his lens, from earlier Greek and Iranian sources), the dynamic tradition of a philosophical-ethical approach to human upbringing and learning continues in the Islamic context into modernity. This fact is best exemplified by the work of the Algerian-French thinker Mohammed Arkoun (1928-2010), who not only conducted much invaluable research on the respective Muslim discourses but became an active voice in them himself through his propagation of an Arabhumanism. This Arab humanism, as Arkoun envisioned it, mirrors that of Miskawayh, most notably in categories like intellectual open-mindedness and a vital engagement to satisfy one’s scholarly curiosity through learning from both inside and outside the intellectual culture of Islam, past and present.

Lastly, the concept of humanism in Miskawayh’s work becomes apparent, not least of all, when we look at the fact that, although Miskawayh spoke in all his works only of the education of boys and men, much of his pedagogical advice, when read in the context of modern societies, expresses universal and gender-unspecific values and ethics of learning.